Study reveals new threat to the ozone layer

“Ozone depletion is a well-known phenomenon and, thanks to the success of the Montreal Protocol, is widely perceived as a problem solved,” says University of East Anglia’s David Oram. But an international team of researchers, led by Oram, has now found an unexpected, growing danger to the ozone layer from substances not regulated by the treaty. The study is published today in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, a journal of the European Geosciences Union.

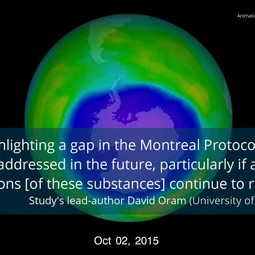

Thirty years ago, the Montreal Protocol was agreed to phase-out chemicals destroying the ozone layer, the UV-radiation shield in the Earth’s stratosphere. The treaty has helped the layer begin the slow process of healing, lessening the impact to human health from increased exposure to damaging solar radiation. But increasing emissions of ozone-destroying substances that are not regulated by the Montreal Protocol are threatening to affect the recovery of the layer, according to the new research.

The substances in question were not considered damaging before as they were “generally thought to be too short-lived to reach the stratosphere in large quantities,” explains Oram, a research fellow of the UK’s National Centre for Atmospheric Science. The new Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics study raises the alarm over fast-increasing emissions of some of these very short-lived chemicals in East Asia, and shows how they can be carried up into the stratosphere and deplete the ozone layer.

Emissions of ozone-depleting chemicals in places like China are especially damaging because of cold-air surges in East Asia that can quickly carry industrial pollution into the tropics. “It is here that air is most likely to be uplifted into the stratosphere,” says co-author Matt Ashfold, a researcher at the University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus. This means the chemicals can reach the ozone layer before they are degraded and while they can still cause damage.

One of the new threats is dichloromethane, a substance with uses varying from paint stripping to agricultural fumigation and the production of pharmaceuticals. The amount of this substance in the atmosphere decreased in the 1990s and early 2000s, but over the past decade dichloromethane became approximately 60% more abundant. “This was a major surprise to the scientific community and we were keen to discover the cause of this sudden increase,” says Oram.

“We expected that the new emissions could be coming from the developing world, where industrialisation has been increasing rapidly,” he says. The team set out to measure air pollution in East Asia to figure out where the increase in dichloromethane was coming from and if it could affect the ozone layer.

“Our estimates suggest that China may be responsible for around 50-60% of current global emissions [of dichloromethane], with other Asian countries, including India, likely to be significant emitters as well,” says Oram.

The scientists collected air samples on the ground in Malaysia and Taiwan, in the region of the South China Sea, between 2012 and 2014, and shipped them back to the UK for analysis. They routinely monitor around 50 ozone-depleting chemicals in the atmosphere, some of which are now in decline as a direct consequence of the Montreal Protocol.

Dichloromethane was found in large amounts, and so was 1,2-dichloroethane, an ozone-depleting substance used to make PVC. China is the largest producer of PVC, which is used in many construction materials, and its production in the country has increased rapidly in the past couple of decades. But the rise in dichloroethane emissions was unexpected and surprising because the chemical is both a “valuable commodity” and “highly toxic”, says Oram. “One would expect that care would be taken not to release [dichloroethane] into the atmosphere.”

Data collected from a passenger aircraft that flew over Southeast Asia between December 2012 and January 2014 showed that the substances weren’t only present at ground level. “We found that elevated concentrations of these same chemicals were present at altitudes of 12 km over tropical regions, many thousands of kilometres away from their likely source, and in a region where air is known to be transferred into the stratosphere,” says Oram.

If the chemicals that were now discovered in unexpectedly large amounts can reach the ozone layer in significant quantities, they can cause damage. “We are highlighting a gap in the Montreal Protocol that may need to be addressed in the future, particularly if atmospheric concentrations continue to rise,” Oram concludes.

###

Please mention the name of the publication (Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics) if reporting on this story and, if reporting online, include a link to the paper (https://www.atmos-chem-phys.net/17/11929/2017/) or to the journal website (https://www.atmospheric-chemistry-and-physics.net).

More information

This research, by scientists in the UK, Germany, Taiwan and Malaysia, is presented in the paper ‘A growing threat to the ozone layer from short-lived anthropogenic chlorocarbons’ to appear in the EGU open access journal Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics on 12 October 2017.

The study was partly funded by the UK Natural Environment Research Council, the Malaysian Ministry of Higher Education (HiCoE Grant IOES-2014) and the Taiwan EPA and MOST. The team used data from the IAGOS CARIBIC project, which is supported by the German Ministry of Education and Science and by Lufthansa, and the measurements were part-funded by the European FP7 programme.

Citation: Oram, D. E., Ashfold, M. J., Laube, J. C., Gooch, L. J., Humphrey, S., Sturges, W. T., Leedham-Elvidge, E., Forster, G. L., Harris, N. R. P., Mead, M. I., Abu Samah, A., Phang, S. M., Chang-Feng, O.-Y., Lin, N.-H., Wang, J.-L., Baker, A. K., Brenninkmeijer, C. A. M., and Sherry, D.: A growing threat to the ozone layer from short-lived anthropogenic chlorocarbons, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 11929–11941, 2017, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-11929-2017, 2017.

The team is composed of David Oram (School of Environmental Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK [UEA]), Matthew Ashfold (University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus, Semenyih, Malaysia), Johannes Laube (UEA), Lauren Gooch (UEA), Stephen Humphrey (UEA), William Sturges (UEA), Emma Leedham-Elvidge (UEA and Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, Mainz, Germany [MPIC]), Grant Forster (UEA), Neil Harris (School of Energy, Environment and Agrifood/Environmental Tech-nology, Cranfield University, UK [Cranfield]), M. Mead (Cranfield and Institute of Ocean and Earth Sciences, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia [Malaya]), Azizan Abu Samah (Malaya), Siew Moi Phang (Malaya), Chang-Feng Ou-Yang (Department of Atmospheric Sciences, National Central University, Taoyuan, Taiwan [DAS-NCU]), Neng-Huei Lin (DAS-NCU), Jia-Lin Wang (Department of Chemistry, National Central University, Taoyuan, Taiwan), Angela Baker (MPIC), Carl Brenninkmeijer (MPIC), and David Sherry (Nolan Sherry & Associates, Kingston upon Thames, UK).

The European Geosciences Union (EGU) is Europe’s premier geosciences union, dedicated to the pursuit of excellence in the Earth, planetary, and space sciences for the benefit of humanity, worldwide. It is a non-profit interdisciplinary learned association of scientists founded in 2002 with headquarters in Munich, Germany. The EGU has a current portfolio of 17 diverse scientific journals, which use an innovative open access format, and organises a number of topical meetings, and education and outreach activities. Its annual General Assembly is the largest and most prominent European geosciences event, attracting over 13,000 scientists from all over the world. The meeting’s sessions cover a wide range of topics, including volcanology, planetary exploration, the Earth’s internal structure and atmosphere, climate, energy, and resources. The EGU 2018 General Assembly is taking place in Vienna, Austria, from 8 to 13 April 2018. For more information and press registration, please check http://media.egu.eu closer to the time of the meeting, or follow the EGU on Twitter and Facebook.

If you wish to receive our press releases via email, please use the Press Release Subscription Form at http://www.egu.eu/news/subscribe/. Subscribed journalists and other members of the media receive EGU press releases under embargo (if applicable) at least 24 hours in advance of public dissemination.

Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics (ACP) is an international scientific journal dedicated to the publication and public discussion of high-quality studies investigating the Earth’s atmosphere and the underlying chemical and physical processes. It covers the altitude range from the land and ocean surface up to the turbopause, including the troposphere, stratosphere, and mesosphere.

Contact

Scientists

David Oram

National Centre for Atmospheric Sciences and Centre for Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences

School of Environmental Sciences, University of East Anglia

Norwich, UK

Phone +44 (0)1603 59 7400

Email d.oram@uea.ac.uk

Matthew Ashfold

School of Environmental and Geographical Sciences, University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus, 43500 Semenyih, Malaysia

Phone +6 (03) 8725 3434

Email matthew.ashfold@nottingham.edu.my

Chang-Feng Ou-Yang

Department of Atmospheric Sciences

National Central University

Taoyuan, Taiwan

Phone +886 (0) 3-422-7151 ext. 65543

Email cfouyang@cc.ncu.edu.tw

Press officer

Bárbara Ferreira

EGU Media and Communications Manager

Munich, Germany

Phone +49-89-2180-6703

Email media@egu.eu

Twitter: @EuroGeosciences

Links

- Scientific paper

- Journal – Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics

- Read this press release in simplified language, aimed at 7–13 year olds, on our Planet Press site