Regular GfGD Blog contributor Heather Britton pen’s this weeks post, where she discusses the heated topic of whether we are, or not, living in the Anthropocene. [Editor’s note: This post reflects Heather’s personal opinion. This opinions may not reflect official policy positions of Geology for Global Development.]

Naming a geological epoch the Anthropocene, literally meaning ‘the recent age of man’, is an idea that has been seriously discussed in many scientific circles and has become a scientific buzzword in recent years. Environmentalists, generally, are great proponents for the idea, stating that it summarises the huge changes that human presence has had on the planet and draws attention to the need for us to change our ways and prevent the damage from extending into the future. Geologists are typically less enthused by the idea. Naming an interval of geological time involves formally recognising that the Earth has been permanently changed at the onset of this era, and although in many ways humans have permanently changed the planet, making this a formal geological epoch requires the identification of a single point in the rock record when this took place. I wish to explain why I believe the Anthropocene, although suggested for admirable reasons, should not become formally recognised.

The term was first popularised almost 20 years ago in the year 2000 (by environmental scientist Paul Crutzen) and in 2016 the Working Group on the Anthropocene (WGA) voted to formally designate the epoch Anthropocene and present the recommendation to the international geological congress. The International Commission on Stratigraphy and the International Union of Geological Sciences have not approved this subdivision of geological time, but it may be that a decision is on the horizon [Ed: In July 2018 the International Union of Geological Sciences ratified a decision by the International Commission on Stratigraphy which announced Earth was living in the Meghalayan Age].

Finding the signal that marks this period exactly is difficult, but not for a lack of options. The prime candidate is the appearance of radioactive nuclides from nuclear bomb tests, which have registered a signal worldwide. Plastic pollution, high level of nitrogen and phosphate in soils from fertilisers and a massive increase in the number of fossilised chicken bones are other strong contenders which appear to define the rise of the human population and civilisation. There is certainly strong evidence to suggest humanity’s effect on the planet is permanent, but are we really in a position to state that the planet has undergone a permanent change when humanity itself is still a blip in geological time? To put it another way, if something were to wipe out the human race tomorrow, there certainly would be a distinctive signal of our presence in the rock record, but due to the tiny fraction of Earth history that we occupy, how can we guarantee that it will endure for long enough to be significant in geological terms?

Plastic in the rock record could used as a marker for the base of the Anthropocene. Credit: Guilhem Amin Douillet (distributed via imaggeo.egu.eu)

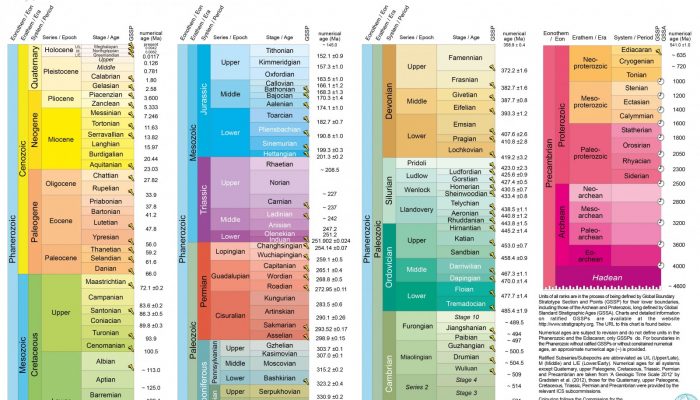

There are many geologists who would claim that the creation of the International Chronostratigraphic Chart is one of the greatest achievements of mankind. Each Eon, Era and Epoch has been painstakingly identified using signals within the strata that must conform to a set of very strict rules. This ensures that rocks all over the world can be correlated to the same record of geological time, allowing communication and understanding between scientists from different countries where otherwise the use of local nomenclature would cause endless mistakes and confusion. The most common way of marking the base of a stratigraphic unit is the appearance or disappearance of a particular fossil.

This method clearly has its limitations – fossil organisms will have only lived in certain habitats, and it is assumed that the time taken for a new fossil organism to spread from where it evolved to locations across the globe is negligible in comparison to geological time, something we can’t be certain is true for all species. Dating is simpler when volcanic rocks are present, as radioactive dating is able to step in and provide, for the most part, accurate rock ages, but such methods cannot be used with any great certainty in the sedimentary world. As discussed above, fossil evidence for the beginning of the Anthropocene is present, but it seems more likely that a different kind of signal is used to mark this new epoch. This would not be the first time, as was demonstrated when the Holocene was formally designated in 2008.

In conclusion, making the Anthropocene a formal geological epoch would send out a message which may fast track the public and global governments to take notice of the impact we are having on the planet and, as a result, take action. I question, however, whether this is a sound enough reason to add to the international stratigraphic column. The Holocene, the time period we are currently considered to be occupying, began approximately 12,000 years ago as Earth slipped out of ice ages into what is currently an extended interglacial period showing no sign of slipping back into its glacial state. The time since the start of the Holocene is already only a geological blink of an eye and cutting it short now to make way for the Anthropocene seems both unnecessary and indicative of a lack of appreciation of the enormity of geological time. The now is not always an appropriate time to mark a significant event, as it is only afterward that its significance can really be properly understood. Regardless of this, it does not excuse how over the miniscule time period that we have spent inhabiting this planet we have had such a detrimental effect on what is a shared home and not ours to ruin. This certainly needs to be put to rights, but I am not certain that announcing the Anthropocene is the best way of doing so.

**This article expresses the personal opinions of the author (Heather Britton). These opinions may not reflect an official policy position of Geology for Global Development. **