February 2021 is an important month for Martian missions, with three arriving at our planetary neighbour within 10 days. Many people have been following the USA’s NASA Perseverance mission, as they landed the new Perseverance rover, with it’s specially designed Ingenuity helicopter in the Jezero Crater in the last 24 hours. Earlier this month the Chinese mission Tianwen-1 also entered the Martian atmosphere to begin the first of a two-part mission to survey the atmosphere from space prior to attempting a rover landing in May, in the Utopia Planitia.

But before either of these missions, the United Arab Emirates successfully maneuvered the Hope Probe from the Emirates Mars Mission into the Martian atmosphere to begin a year-long, in-depth survey of the Martian atmosphere. We were lucky enough to speak with two of the lead scientists, Dr Hessa Rashid Al Matroushi, the Deputy project manager and science, data and analysis lead for the Hope Probe Mars Mission at the Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Center and Dr David Brain, an associate professor at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) at the University of Colorado, Boulder, about the mission, what they hope to learn, and what it means as the first Martian mission launched by an Arabic nation.

Last week the Hope satellite successfully entered into orbit around Mars. Why is this such a challenging step? Were you worried that it might not succeed?

Hessa Al Matroushi: Mars Orbit Insertion is a complex manoeuvre, where Hope rapidly decelerates for a duration of around 27 minutes, firing all six of its Delta-V thrusters, to slow the spacecraft from its cruising speed of 121,000 km/h to around 18,000 km/h to enter a stable orbit around Mars. Mars Orbit Insertion is one of the most critical phases of the mission and there is a 22-minute two-way radio delay between Earth and Hope Probe. Thus, the spacecraft had to be autonomous during this period. While we were both nervous and excited during this time, we knew that the team had prepared for all the possible scenarios ahead.

What is the main scientific objective of the Emirates Mars Mission?

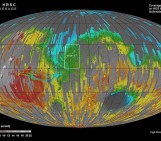

David Brain: The mission will study the Martian atmosphere as a system, with three main science objectives. First, measurements from Hope will be used to determine how the lower atmosphere varies geographically, over the course of a day, and from season to season. Second, Hope measurements will be used to determine how conditions throughout the atmosphere influence the escape of thermal and photochemical atmospheric particles to space. Third, Hope measurements will be used to determine how the uppermost layer of the atmosphere (the exosphere) varies with time and from region to region.

What is special about the Emirates Mars Mission compared to other Martian explorations so far?

David Brain: There are many ways that the mission is unique, but this can probably be said of all missions. Two especially striking aspects from my perspective are the partnership and the orbit.

The mission partnership required engineers and scientists to work together who were sometimes 11 time zones apart and other times working elbow to elbow, in a knowledge transfer partnership nominally for Emirati scientists and engineers, but where all participants ended up learning. I’m not sure there’s previously been a partnership like it on a space exploration project of this scale, and it might provide an example for future international collaborations. This team developed and assembled a spacecraft, testing it on two continents and then getting it to the launch pad on a third continent – all during a global pandemic where international travel could have severely impacted our schedule.

Hope’s orbit is also very unique and enables the mission science. The orbit is much larger than previous spacecraft mission orbits, allowing global views of an entire hemisphere of Mars with every observation. Unlike most previous spacecraft measuring the atmosphere, the orbit is roughly equatorial, allowing measurements of the atmosphere at all times of day. And the orbit is elliptical enough that the probe alternates between “hovering” near a single local time while many geographic regions rotate underneath and “orbiting above a single geographic region” as it experiences different times of day.

Hessa Al Matroushi: Most of the Mars diurnal (i.e., day-to-night) cycle is unexplored over much of the planet. This data is crucial for understanding global circulation and the transfer of matter and energy from the lower-middle atmosphere to the upper layers and out to space. It is still unclear how and when Mars transitioned from a thicker atmosphere billions of years ago to the cold, thin, arid atmosphere we see today. Emirates Mars Mission will be the first to give a truly global picture of the Martian atmosphere.

Many of the other Martian missions have focussed on the planet’s surface; why has this one chosen instead to examine Mars’ atmosphere?

David Brain: There are many outstanding unsolved science questions about Mars, and the community actively maintains a list of scientific priorities for the planet – including priorities for Martian climate, geology, the search for life, and preparation for human exploration. New measurements that helped advance the big questions in any of these areas would have been useful. Our group chose to focus on the atmosphere and climate for a few reasons, including (1) the relative scarcity of atmospheric data for Mars (especially at all times of day), and (2) the idea that we could reduce risk to the mission by making the kinds of measurements that have been made before at Mars but combine them in a new way to enable fundamental new understanding.

When the two-year mission ends, what will happen to the satellite?

David Brain: The orbit of the probe is sufficiently large that there will be no significant degradation of the orbit over very long periods of time. So the probe will continue to orbit Mars well beyond our lifetimes! After the nominal two-year science mission ends, there is an option for an extended mission of two more years of science observations.

The Emirates Mars Mission has provided many opportunities for Early Career Scientists and aims to continue to inspire young people in Arabic countries to get involved in science and technology (Photo credit: MBRSC)

This is the first mission to Mars that has been sent by an Arab nation. Beyond the mission’s scientific and technological achievements, what does this mission’s success mean societally, both for the UAE and the world?

Hessa Al Matroushi: The Emirates Mars Mission represent the Emirates’ vision for the future where the knowledge and capabilities of those in the Emirates are the wealth of the nation, in addition to, being the source of stability and readiness of tomorrow’s challenges and opportunities. The Emirates Mars Mission is not about sending a probe to Mars; but it’s about the journey of developing our capabilities in interplanetary missions. As the probe was named ‘Hope’, it indicates that the mission represents a greater hope for the region: an inspiration to the youth to engage in the fields of science and technology and to have always overarching goals.

Can you tell us more about the science apprenticeship scheme, and what it means for Early Career space scientists?

David Brain: Yes! One of the other goals of the mission is to train and prepare Emirati scientists, and the mission science team has been actively involved with this in a variety of ways, ranging from hosting summer undergraduate students on research projects, to running short courses for Emirati students and engineers, to establishing Master’s programs for interested Emirati engineers working on the mission.

The apprenticeship program is another example. Several Emirati engineers have been training as instrument scientists for the mission over the past several years, to prepare to work with mission data as it becomes available. These engineers have been mentored by other scientists on the team as they analyzed models and data sets analogous to what will be available from the mission. There has also been active engagement with K-12 students in the Emirates, and with Emirati universities. All of these programs share at least some common goals: exciting young Emiratis about science (and space science specifically) and highlighting this as a possible career path. The opportunity to excite young people about science has been a very exciting part of the mission for me. Watching those young scientists as they join our community and help us make progress on important questions will be very rewarding.

Following the initial successes of the deployment of the Hope Probe, what are your hopes for the future of Martian research?

Hessa Al Matroushi: At the moment, the Hope Probe is in a capture orbit around Mars where we are checking out our instruments and calibrating them before we transition to the science orbit in April this year. I’m looking forward to start the science phase, which will last for one Martian year, so we begin analyzing the data returned from the mission We are excited as well to share this data with all the science community and interested researchers through an online platform free of charge, so we all embark on an exciting journey to explore the secrets of our neighboring planet.

Thank you to Dr Hessa Rashid Al Matroushi and Dr David Brain for answering our questions!

For more information and to stay up to date with the progress of the Emirates Mars Mission, check their website.

Interview by Hazel Gibson, EGU Communications Officer.