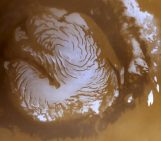

“I did not know that there is water on Mars!” This a sentence I hear surprisingly often when I talk about glaciers on Mars. In fact, it has been known for some time that water exists in the form of ice and water vapour on the planet. For example, water ice layers several kilometres thick cover the Martian poles, and the ground close to the Polar Regions has permafrost patterns very similar to what we see on Earth.

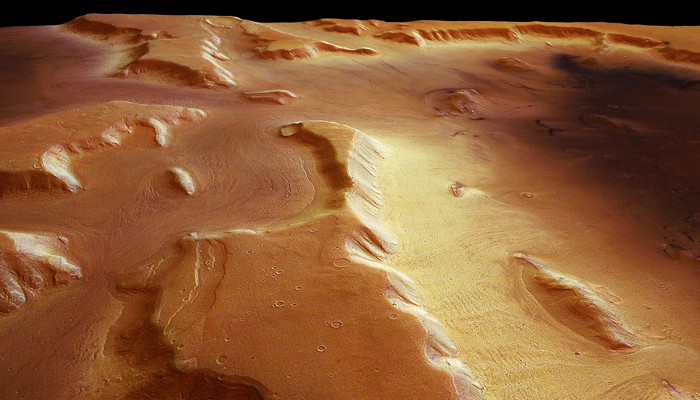

The glaciers on Mars were discovered in the 1970s on images from the Viking missions. From the images it was evident that features made up of a soft, deforming material existed in some parts of the planet. At the time, it was suggested that the features might consist of a mixture of water ice, CO2 ice or perhaps mud.

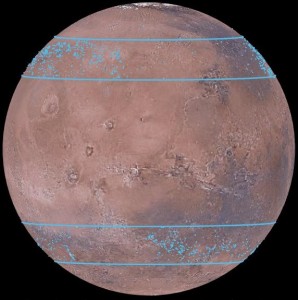

More than 10,000 water ice bodies (blue dots) have been found between 30 and 50 degrees (blue lines). Credit: Mars Digital Image Model, NASA/J. Levy/Nanna B. Karlsson

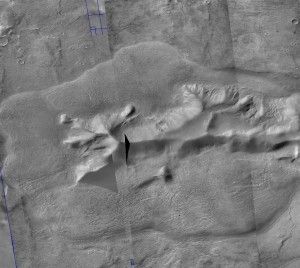

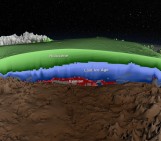

In 2005, NASA launched the satellite Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter that carried amongst other instruments the SHARAD (SHAllow RADar) sounder. The instrument emitted radar waves that could penetrate the surface of the planet, and return information on what was below the dusty surface. The mission proved successful and – amongst many other discoveries – the SHARAD measurements showed that the glaciers consist of more than 90% water ice .

We now know the composition of the glaciers but many questions remain. One extremely interesting observation is the fact that the glaciers are only found in particular latitude bands: between 30 and 50 degrees on both hemispheres. A recent study has mapped more than 10,000 features in these latitudes. In other words, the glaciers are much more abundant than initially thought, but why are they there in the first place? The answer is probably to be found somewhere in Mars’s past. More than 5 million years ago, the amount of solar insolation at the poles of Mars was dramatically different compared to today. Models have shown that during this time water ice at the poles would have been unstable and possibly migrated to the midlatitudes. When the climate changed, again the water migrated back to the poles. The glaciers could therefore be remnants of a past, large ice sheet.

How much water do the glaciers contain then? To answer this question, we can use knowledge of glaciers on Earth. A glacier is essentially a big chunk of ice, and when it flows, it obtains a shape that tells us something about how soft the ice is. Water ice moves and deforms in a certain way, and the slope of the surface of a glacier therefore reveals information about the bed under the glacier. Looking at images of the Martian surface, we can see where the glaciers are, and from the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter we know the surface elevation. This allows us to setup models for how the ice behaves on Mars.

Combining the models with the radar measurements and maps of the glaciers, it turned out that the glaciers contain more than 150 thousand cubic kilometres of ice. This amount of ice may cover the surface of the planet in a 1.1 metres thick ice layer.

If you want to know more about glaciers on Mars check out my recent paper published in Geophysical Research Letters. You can also meet me at the EGU General Assembly next week and listen to my talk at 8:30am, Wednesday the 15th of April in Room R13 (Session CR6.1Modelling ice sheets and glaciers).

Pingback: » What’s up? The Friday links (77)