Three years ago, an earthquake-induced avalanche and rockfalls buried an entire Nepalese village in ice, stone, and snow. Researchers now think the region’s heavy snowfall from the preceding winter may have intensified the avalanche’s disastrous effect.

The Langtang village, just 70 kilometres from Nepal’s capital Kathmandu, is nestled within a valley under the shadow of the Himalayas. The town was popular amongst trekking tourists, as the surrounding mountains offer breathtaking hiking opportunities.

But in April 2015, a 7.8-magnitude earthquake, also known as the Gorkha earthquake, triggered a massive avalanche and landslides, engulfing the village in debris.

Scientists estimate that the force of the avalanche was half as powerful the Hiroshima atomic bomb. The blast of air generated from the avalanche rushed through the site at more than 300 kilometres per hour, blowing down buildings and uprooting forests.

By the time the debris and wind had settled, only one village structure was left standing. The disaster claimed the lives of 350 people, with more than 100 bodies never located.

Before-and-after photographs of Nepal’s Langtang Valley showing the near-complete destruction of Langtang village. Photos from 2012 (pre-quake) and 2015 (post-quake) by David Breashears/GlacierWorks. Distributed via NASA Goddard on Flickr.

Since then, scientists have been trying to reconstruct the disaster’s timeline and determine what factors contributed to the village’s tragic demise.

Recently, researchers discovered that the region’s unusually heavy winter snowfall could have amplified the avalanche’s devastation. The research team, made up of scientists from Japan, Nepal, the Netherlands, Canada and the US, published their findings last year in the EGU’s open access journal Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences.

To reach their conclusions, the team drew from various observational sources. For example, the researchers created three-dimensional models and orthomosaic maps, showing the region both before it was hit by the coseismic events and afterwards. The models and maps were pieced together using data collected before the earthquake and aerial images of the affected area taken by helicopter and drones in the months following the avalanche.

They also interviewed 20 villagers local to the Langtang valley, questioning each person on where he or she was during the earthquake and how much time had passed between the earthquake and the first avalanche event. In addition, the researchers asked the village residents to describe the ice, snow and rock that blanketed Langtang, including details on the colour, wetness, and surface condition of the debris.

Based on their own visual ice cliff observations by the Langtang river and the villager interviews, the scientists believe that the earthquake-triggered avalanche hit Langtang first, followed then by multiple rockfalls, which were possibly triggered by the earthquake’s aftershocks.

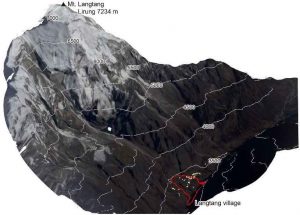

A three-dimensional view of the Langtang mountain and village surveyed in this study. Image: K. Fujita et al.

According to the researchers’ models, the primary avalanche event unleashed 6,810,000 cubic metres of ice and snow onto the village and the surrounding area, a frozen flood about two and a half times greater in volume than the Egyptian Great Pyramid of Giza. The following rockfalls then contributed 840,000 cubic metres of debris.

The researchers discovered that the avalanche was made up mostly of snow, and furthermore realized that there was an unusually large amount of snow. They estimated that the average snow depth of the avalanche’s mountainous source was about 1.82 metres, which was similar to snow depth found on a neighboring glacier (1.28-1.52 metres).

A deeper analysis of the area’s long-term meteorological data revealed that the winter snowfall preceding the avalanche was an extreme event, likely only to occur once every 100 to 500 years. This uncommonly massive amount of snow accumulated from four major snowfall events in mid-October, mid-December, early January and early March.

From these lines of evidence, the team concluded that the region’s anomalous snowfall may have worsened the earthquake’s destructive impact on the village.

The researchers believe their results could help improve future avalanche dynamics models. According to the study, they also plan to provide the Langtang community with a avalanche hazard map based on their research findings.

Further reading

Qiu, J. When mountains collapse… Geolog (2016).

Roberts Artal, L. Geosciences Column: An international effort to understand the hazard risk posed by Nepal’s 2015 Gorkha earthquake. Geolog (2016).