Barcelona is a vibrant city on the Mediterranean coast, nested snugly between the sea and the Collserola Ridge of the Catalan Coastal ranges. The story of Barcelona starts around 2000 years ago as an Iberian settlement, owing to its strategic location on the coastal route connecting Iberia and Europe. The combination of easily defendable ground and the fertile soils of the Besos and Llobregat deltas have helped shape its history as an important trade hub and place of varying political importance. However, the rocks on (and of) which the city is built tell a much longer and intriguing story. Today we take a close look at the rocks that built Barcelona, and the fascinating history that produced them.

Our story begins in the Paleozoicum, when the oldest rocks outcropping near Barcelona were formed. Iberia collided with the remains of Gondwana and became part of the supercontinent Pangea. During this period, the Hercynian orogeny, intense metamorphism produced part of the rich mineral assemblage found in the Collserola Ridge today (although it should be noted that collecting rocks is forbidden, as the ridge enjoys a Natural Park status). During the Mesozoic, when Pangea broke apart and Iberia developed into a separate plate, the area that is now Catalunya was mostly submerged under a sea. Most of the sediments deposited during this stage have however been eroded away. This was due to the uplift of the Coastal Ranges during the Pyrenean orogeny in the Paleogene, as Iberia reconnected with Europe between 55 and 25 million years ago. The Catalan Coastal Range was rotated anticlockwise, making it run oblique to the N-S contraction in the Pyrenees. As a result of this uplift, the Collserola Ridge still has an elevation of up to 500 meters, providing sweeping vistas over the city and Mediterranean. During the middle Miocene (around 14 million years ago) the current Barcelona was a coastal area, where the erosional products of the Coastal Ranges were deposited under varying sea levels. Extension started in this period, and continues up to today along reactivated normal faults associated with the Valencia Trough.

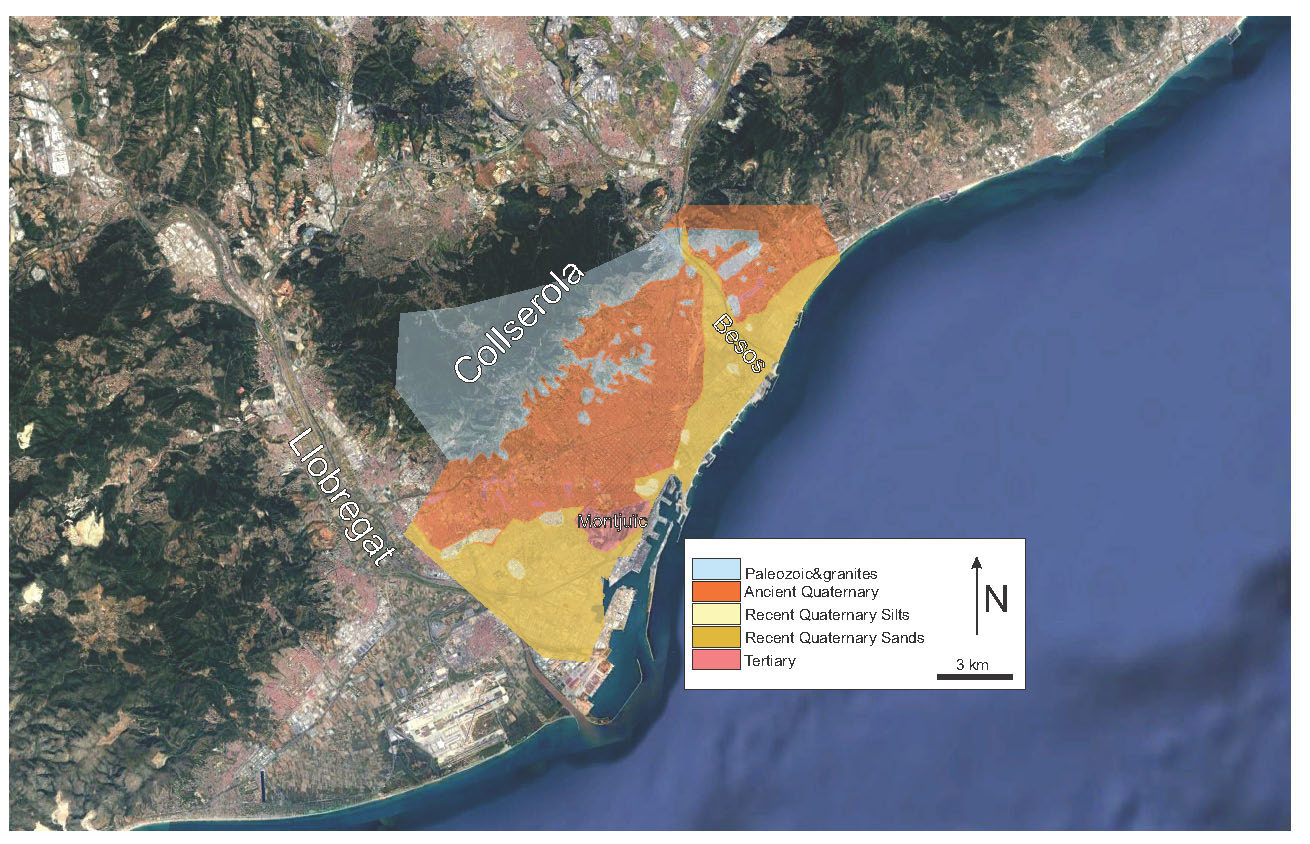

This geological map shows the modern city and the distribution of bedrock types underlying it. Credit: Google Earth, Geological Map adjusted from Sergisai.

Montjuïc – foundations and façades

So how has this geological history affected the city of Barcelona? The most obvious influence is in the very materials used for constructing it, leaving clues to the geological history of Catalonia all over the city. Situated to the south of Barcelona’s centre is Montjuïc, a ~200 m high block of Tertiary deltaic sediments, product of erosion from the Collserola mountains. The block was tilted due to recent extension, and the surrounding materials eroded, leaving it as an isolated hill surrounded by the alluvial plain filled with modern sediments.

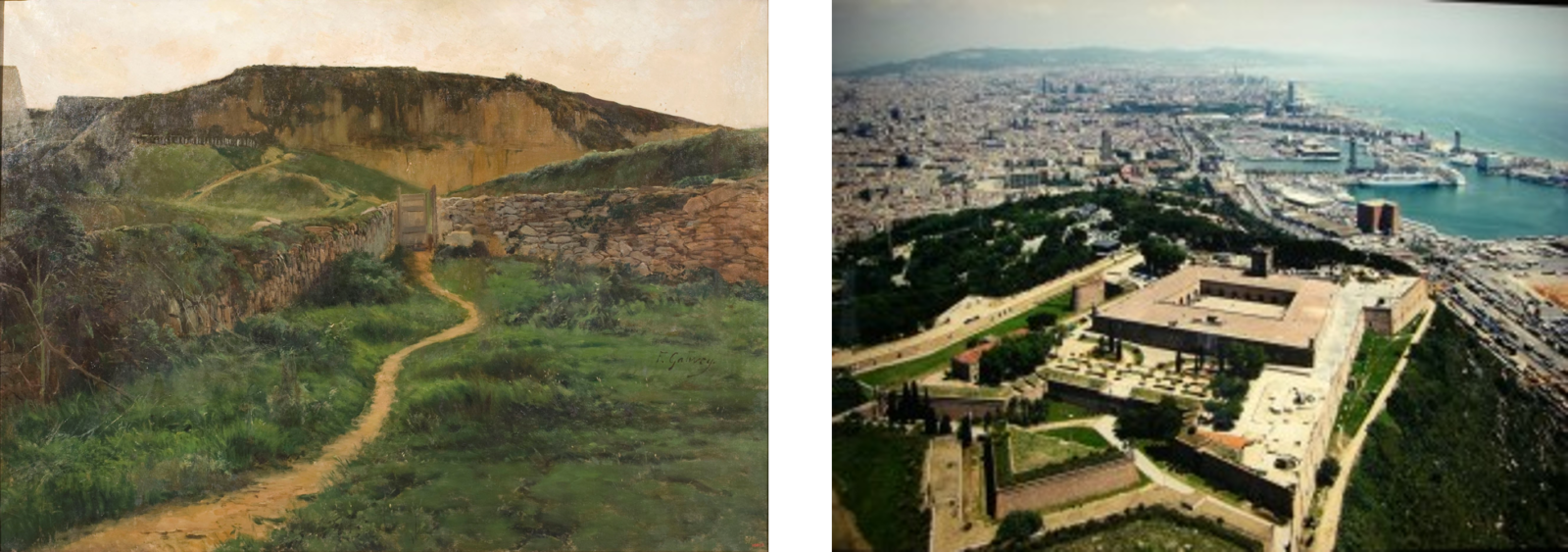

Left: Study of Montjuïc Quarry Artists: Enric Galwey, Barcelona, 1864-1931. Credit: Museu Nacional. Right: View of Montjuïc castle. Credit: barcelonaconnect.com

On top of the Montjuïc hill sits an imposing castle with 360o views over the city, built in the seventeenth century. It was used for defensive purposes, for example as a base by Catalan forces fighting a Spanish army during the Battle of Montjuïc in 1641, but also to control the city itself, being used for bombardments and imprisonment at various occasions since the fall of Barcelona during the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714). Its bloody history continued into the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). Montjuïcs most important mark on the city however has been the sandstone quarried there and used in many of Barcelona’s most iconic structures. The very short distance from the source area has caused a rich and poorly sorted mineral assemblage, with the metamorphic minerals of the Collserola Ridge somewhat preserved. The sediments are a sequence of conglomerates, sandstones, mudstones and marls due to the changing sedimentary conditions with variation of sea levels. Although the main mineral assemblage is quartz and feldspars, it includes small amounts of biotite, muscovite, zircon, chlorite and tourmaline, adding to the vibrant colours of the sediments. Montjuïc stone’s high silica content (making it exceptionally durable) and vibrant colours made it a cherished resource, therefore being quarried from Iberian times well into the 20th century. Amongst others, the Palau de la Genaralitat, City hall, Catedral de Barcelona and Barcelona University were constructed from Montjuïc stone. A notable example is the Santa Maria del Mar church, of which the construction formed the backdrop for the 2006 novel (and 2018 Netflix drama) by Idefonso Falcones, La Catedral del Mar, telling the story of a stoneworker and illuminating the hardships and triumphs of medieval life in Barcelona.

Antoni Gaudí – the modern face of Barcelona

House Casa Mila (La Pedrera) in Barcelona building by the great Spain architect Antonio Gaudi. Credit: Adobe Stock.

Apart from the materials found in Barcelona’s buildings, their design has also been influenced by the impressive geology found on the Iberian peninsula. The most obvious example of this is found in the works of Antoni Gaudí, the architect who has had perhaps the biggest single-handed influence on the face of the city.

Besides from his most famous works, the (still unfinished) Sagrada Família Cathedral, Casa Battló, Casa Milà and Parc Güell, he designed about ten more iconic buildings, and hundreds of other objects. Part of his architectural genius came from the inspiration he pulled from landscapes surrounding Barcelona, leading him to become one of the founders of the school of organic architecture. The Prades Mountains in the region of Terragona bear a striking resemblance to some of the design element used in Casa Battló and La Pedrera,while the beautiful l´Argenteria in the Collegats gorge in the Pyrenees has been rumoured to have inspired the Nativity façade of the Sagrada Familia (see the photos below). The gorge was incised into Tertiary conglomerates deposited on the interface between the (then endorheic) Ebro Basin and the Pyrenees, subsequently affected by karstification and finally covered in travertine precipitated from natural spring water, resulting in this spectacular geological feature. Gaudi’s works give the city an unique and organic feel, and form part of the main tourist attractions.

Left: L’Argenteria, Colgats gorge. Right: Nativity Façade of the Sagrada Familia. It is easy to see how Gaudi could have drawn inspiration from the beautiful cliff for some of the elements of the façade. Credit: Chris Kuijper.

As with most modern cities, the geological features visible in Barcelona are only a tiny fraction of the richness of rocks and structures hidden underground and as the city rapidly expanded in the 20th century, very little of this information was properly recorded. But, a curious eye and wandering feet can discover many clues to the rich history of the region, and any travelling geologist would be more than satisfied with what Barcelona has to offer.

Sacha

Loved the part about Gaudi, great read Hanneke!