Why are glaciers important?

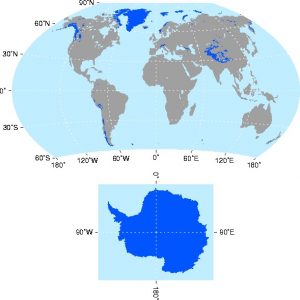

Glaciers cover around 10% of the global land surface. This includes the large ice sheets (e.g. in Greenland and Antarctica) as well as smaller ice caps and valley glaciers (e.g. in Iceland, Norway and New Zealand). Figure 1 shows the current distribution of glaciers around the world.

Figure 1 – The global distribution of glaciers around the world from the GLIMS glacier database. Source: https://nsidc.org/glims/

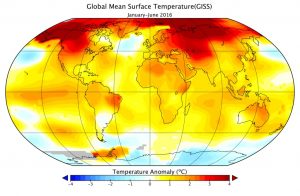

Glaciers play an important role in moderating global and local climate, but they are very sensitive to changes in climatic conditions. Currently, around 90% of the world’s glaciers are retreating. Under current IPCC predictions of future global warming and climatic changes, many glaciers will have disappeared by 2100. Figure 2 shows the temperature for different parts of the globe in 20167 relative to average (‘normal’) values. Red and yellow colours mean that temperatures are hotter than usual, and it is clear that most of the world is warming. The Arctic is warming especially quickly, and is several degrees (°C) warmer than normal. Glaciers here will therefore be especially sensitive to climate change.

Figure 2 – Global average (mean) surface temperature January-June 2016 relative to long-term conditions. Red and yellow colours indicate higher temperatures than normal. Source: https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/12305

Glaciers contain around 75% of the world’s freshwater. Many of the world’s rivers are fed by meltwater from glaciers and mountain snowpacks. These include major rivers such as the Ganges and Brahmaputra, where meltwater from Himalayan glaciers and snow makes its way downstream and, together with river water from other sources such as monsoon rains, eventually supplies over 1 billion people.

What are the key issues?

As climate change continues, and global air temperature rise leads to enhanced glacier melt, there are a number of key considerations:

How will glaciers respond to climate change? – Will they disappear?

How will glacier melt affect water flow downstream?

How quickly might these changes happen?

How will glacier melt affect river systems?

Here we consider some of the impacts of glacier retreat on river flow, but there are also many other impacts, including: changes to river water chemistry, and impacts on ecosystems – the plants and animals living in and around the rivers

- Turning on the tap

Increased glacier melt produces more meltwater, which means that rivers will have a higher flow and more water will be transported downstream. However, this situation is likely to last only temporarily, because…

2. Turning off the tap

Eventually (usually over several decades or longer), if a glacier melts fully, there will be no meltwater feeding into rivers downstream. Some rivers, that are fed by water from multiple sources (such as rainfall) do not rely on glacial meltwater and will not be greatly impacted by the disappearance of glaciers in their headwaters. Other rivers, especially those in mountain catchments, are supplied only by snow and ice melt. The disappearance of glaciers would therefore have major impacts on their water supply – the equivalent of turning off a tap. We know that many glaciers are melting rapidly, and some are predicted to have disappeared over the next few decades.

3. Changing lanes

In some places, as a glacier retreats, the meltwater streams may change course entirely and flow in a different direction. This has been seen recently in Alaska, where meltwater from the Kaskawulsh glacier has undergone a major transformation in its drainage pathway in the space of only four days. Meltwater previously flowed northwards, supplying the Slims River, but recent glacier retreat has caused a shift in the drainage pathway, and it is no longer favourable for the water to flow north, and the Slims has almost entirely disappeared. Instead, meltwater has been diverted towards the south to the Alsek river. This event has highlighted that major transformations in glaciers and river systems, in response to climate change, can happen in the blink of an eye. See a full news report on the changes here and the full research article here.

4. The four seasons

Climate change can also affect seasonality – the timing and duration of the seasons in a year. For example, with increased global warming, we might expect some parts of the planet to experience a longer warm season. Climate change might also affect the duration and intensity of precipitation (e.g. rain and snowfall) events and storminess. Changes in seasonality are already being felt in some parts of the world. In some parts of the Arctic, the Spring melt season, and therefore the onset of river flow, is starting earlier than it has done in the past. Such changes will influence when and in what quantities meltwater is transported downstream. Continued monitoring of climatic conditions, glacier and river behaviour will allow us to more fully understand the changes that are occurring in glacial environments in response to global temperature rise.

In summary

- We know that global climate change is influencing glacier behaviour. Some glaciers are responding rapidly to climate change – over years and decades – and many will have melted completely by 2100.

- As glaciers melt they produce more meltwater, which increases the flow of river systems downstream.

- But if glaciers melt entirely, the meltwater ‘tap’ will be switched off. This may have major impacts on river systems that rely on meltwater inputs – such as in high mountain regions where meltwater is the dominant source of river water.

- We have seen recently in Alaska, that glacier retreat can cause meltwater drainage to change direction in a matter of days.

- Understanding glacier and river response to climate change is therefore key for our ability to prepare for future scenarios.

Helpful resources

The following links provide information, data, graphics, and videos about glaciers, glacier melt, meltwater, and climate change. There is something suitable for all age groups.

National Snow and Ice Data Centre https://nsidc.org/

NOAA http://www.noaa.gov/

INTERACT Arctic Monitoring programmes http://www.eu-interact.org/

NASA Climate https://climate.nasa.gov/