Earthquakes: what’s happening in central Italy?

3 November 2016

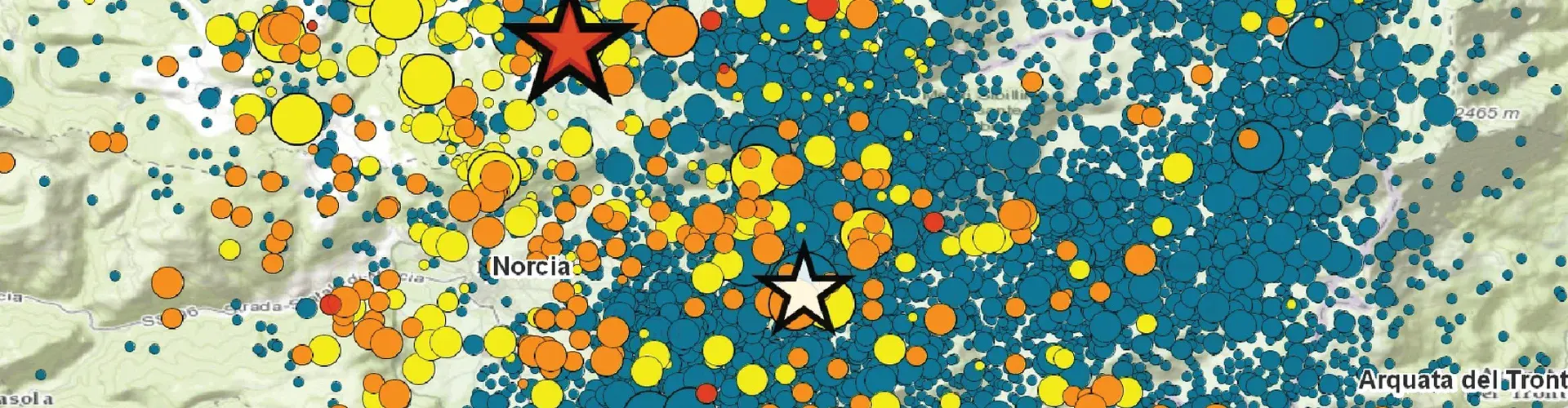

On Sunday 30 October 2016 at 7:40 am local time, a magnitude 6.5 earthquake hit central Italy near Norcia. According to the European-Mediterranean Seismological Centre, the epicentre was at 42.84 N, 13.11 E at a depth of about 10 km. Earlier today, another strong (magnitude 4.8), shallow earthquake hit the area.

Some 300 people died in the same region when an earthquake of magnitude 6.2 struck in late August. The area was also affected by two magnitude 5.5 and 6.1 earthquakes last week, and by hundreds of tremors over the past few months. The devastating M 6.3 earthquake of April 6, 2009 in L’Aquila happened only about 50 km to the south of these very recent earthquakes.

Sunday’s earthquake, the most powerful in Italy since 1980, left over 15,000 people homeless. Despite the extensive damage to buildings, no casualties have been confirmed so far, in large part because the region had been evacuated following last week’s events.

Italy’s Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV), in Rome, published a preliminary report about the characteristics of this latest earthquake, including information about historical seismicity and earthquake fault geometry and slip. Detailed analysis of seismic data will clarify how this earthquake relates to others in the region and which part of the complex fault system in central Italy was activated.

Aldo Zollo, Professor of Seismology at the University of Naples Federico II, says: “This event likely ruptured an about 20 km fault segment, north-west of the previous main shocks in August and October. The peak-ground-acceleration maps suggest a rupture of the fault system in the South-East direction. The fault strike is oriented along the Apennine chain axis, similar to the previous earthquake fault directions.”

Antonella Peresan, Earthquake Hazards Science Officer of the Natural Hazards Division and a seismologist at Italy’s Istituto Nazionale di Oceanografia e di Geofisica Sperimentale in Trieste says: “The large quakes that struck this region during the last months (possibly even longer, and on a larger scale, starting with the L’Aquila earthquake in 2009) can hardly be considered as independent events. Also, the recent quakes were not coming totally unexpected. Given the features of seismicity in the area, often characterised by double events and sequences of rather strong earthquakes, the likelihood of further quakes was relatively high according to different statistical and geophysical models.”

Zollo says: “The occurrence of multiple shocks during past earthquake sequences in Italy is not a rare event. We recall Irpinia in 1980, Abruzzo in 1984 and more recently Colfiorito in 1997 and L’Aquila in 2009. The difference in all these earthquake sequences is the time delay between strongest shocks, which can vary between days and months as in the actual earthquake sequence, hours in the Colfiorito earthquake and even tens of seconds as for the M 6.9 Irpinia earthquake.”

“The Central Apennines are densely faulted, and the probability that a rupture on a given M-about-6 fault segment (approximate length of 10 km) can trigger a new rupture on adjacent, similar size segments is relatively high, provided that stress distribution, friction and geometrical conditions are favorable.”

The ‘fault unzipping’ that we currently experience in Italy can be understood in terms of stress redistribution during earthquakes. For such intense earthquake activity, with multiple damaging events occurring close to each other in space and time, the term ‘earthquake storm’ was coined by Amos Nur, Professor Emeritus of Earth Sciences at Stanford. However, to precisely estimate how and where exactly stress first accumulates and is then released on nearby fault segments requires detailed knowledge about fault structure, geology, and seismicity. This information can then be input into computer simulations to estimate the likelihood of failure (i.e. an earthquake) on known fault structures in the region. Yet, there may be hitherto unmapped geological fault structures, hidden under the Earth surface, that would affect such calculations and corresponding estimates of failure probabilities.

According to seismologists Ross Stein, Volkan Sevilgen and David Jacobson, writing on the Temblor blog, “the Norcia, Gorzano, Capitignano Faults could now be the next domino pieces to fall.” The time when they will fall, however, is largely unknown. In addition, we stress that this is only one possible interpretation of what the models are telling us.

The information above was compiled with the help of officers from the EGU Natural Hazards and Seismology divisions. Special thanks to Martin Mai, Seismology Division President, Aldo Zollo, Real-Time Seismology and Early Warning Science Officer of the Seismology Division and Antonella Peresan, Earthquake Hazards Science Officer of the Natural Hazards Division.

Contact

Bárbara Ferreira

EGU Media and Communications Manager

Munich, Germany

Phone +49-89-2180-6703

Email media@egu.eu

X @EuroGeosciences

Links

- European-Mediterranean Seismological Centre information about Sunday’s earthquake

- European-Mediterranean Seismological Centre information about the earthquake sequence in central Italy

- INGV page for Sunday’s earthquake (in Italian)

- Temblor blog post about Italy’s earthquakes

- Ground displacements caused by Sunday’s earthquake, as measured by the Sentinel satellites

- Peak ground acceleration maps for Sunday’s earthquake

- GFZ GEOFON Global Seismic Network event page for Sunday’s earthquake