Paris, 2000 ya. Claude is sweating all over. It’s mid-July and the sun is burning on his skin. With his hammer and shovel he is digging up grey and white stones. The faults and fractures in the rock help him to get the rocks out easily. But still, it’s hot and humid and his shift isn’t over yet. Luckily he can’t complain about the view. Lutetia, one of the new Roman settlements lies right in front of him, on the left bank of the Seine river.

Paris, 700 ya. Pierre sighs out deeply, his back hurts, but he has to continue. In the small corridors of the underground quarries at Montrouge south of Paris, he is digging for gypsum and cutting limestone for building material. The quarries are narrow and low, so he has to bend over all the time. Mining gypsum is easier, it’s a softer material. It’s the limestone that makes him suffer.

Paris, 300 ya. Jean covers his mouth. The stench is unbearable! Over 12 generations of Parisians are buried at the cemetery ‘Les Innocents’ in the heart of Paris. Last week, the cellar of a house located below the cemetery collapsed under the weight of the buried. The king decided to close all cemeteries within the city centre and so the cemeteries are being emptied. Jean found a job in this chaos, pulling a wagon at night, from the cemetery to entrance of the old, abandoned quarries south of the city.

Figure 1. Geological map of France. The Paris basin is outlined in red and Paris (the red dot) is located at the centre of the basin. Credit: Written In Stone blog

Paris, 200 Ma – today

Paris is located at the heart of the Paris Basin, a NW-SE trending oval feature that measures over 140.000 km2 and extends into the United Kingdom (Figure 1). The basin is positioned on top of a Palaeozoic crystalline basement. The lower lithologies are marine and continental sediments of Permian and Mesozoic age. A major subaerial, Palaeocene erosion event was followed by the deposition of Eocene limestones that is known now as ‘Parisian limestone’. The beige-white rocks are among the most famous building materials that is nowadays exported all over the world, but they used to be the main building material that characterizes the city of Paris. Of course, it is no coincidence that these rocks are of ‘Lutetian’ age, as Lutetia was the Latin name for Paris. The Lutetian is followed by the Bartonian stage, in which gypsum was deposited in the Paris basin, the second most important material that was mined in the Paris region. Oligocene, Miocene and Neogene successions consist of sands, marls and clays and cover all older sediments.

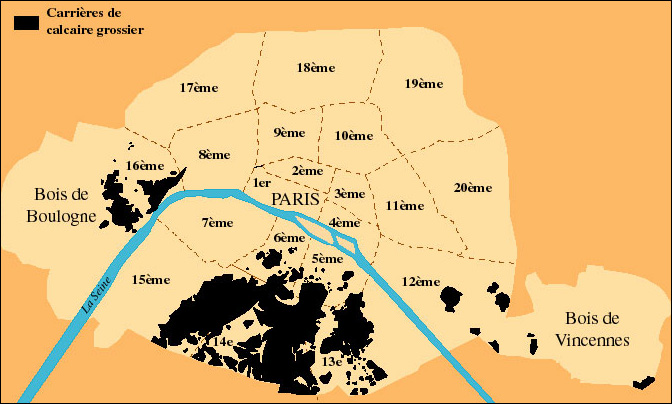

The familiar light-coloured, 6-7 stories high buildings, decorated with balconies and ornaments are Paris’ most famous selling point. Throughout the 20 districts all kinds of structures can be found that are made from these rocks; from regular houses to famous sights, such as the Notre Dame and the Louvre Museum. The rocks do not come from far. Scattered through the city, old quarries can be found above and below the ground (Figure 2). They were intensively mined from 2000 years ago until the 17th century to provide building material for the city of Paris.

Figure 2. Map of Paris with in black the old limestone quarries. Gypsum was mined around Mont Montmartre (18th arrondissement) and Belleville (19th and 20th arrondissement). Credit: Papyserge blog.

The very first mining activities in Paris were in an ‘open-pit’ kind of fashion, as our friend Claude from the introduction experienced. Paris was relatively small and these quarries were located just outside the old city walls. From some of them, we can still see signs nowadays, like the ‘Arènes de Lutèce’, situated in the 5th arrondissement. This was an open-pit mine that later turned into a small Roman amphitheatre (Figure 3).

Figure 3. ‘Les Arènes de Lutèce’. Before this place turned into an amphitheatre for the amusement of the Roman people it served as a limestone quarry to provide building material. Credit: Anouk Beniest.

As Paris expanded, more building material was needed. Even though the already excavated blocks were re-used, underground quarries for limestone and gypsum emerged below Montrouge (14th district), Parc Montsouris (13th district), Parc Butte-Chaument (19th district) and Montmartre (18th district). People like Pierre were subsurface miners. Initially they only excavated the Lutetian limestones. Later also Bartonian gypsum was extracted. Eventually the quarries moved south of Paris, outside the present-day city-limits, leaving a whole network of galleries and corridors below the city (Figure 4).

These quarries below Paris were almost forgotten, as they were abandoned for several decades. When the largest cemetery in the city-center of Paris, ‘Les Innocents’, collapsed and conditions became untenable, the king decided to clear all cemeteries within the citywalls. Our friend Jean was paid for his duties, moving carriages full of bones to the southern end of the quarries, close to the present-day entrance of the catacombs at ‘Denfert-Rochereau’. The major clean-up took a year-and a half during the end of the 18th century and resulted in corridors full of nicely stacked bones, decorated with skulls (Figure 5). During a second wave, more cemeteries were emptied in the early 19th century. Even after World War II, the old quarries at Pièrre-Lachaise were used as final resting place of the thousands of Parisians that found death during the war.

Figure 4 (left). One of the restored quarries below Paris. The pillars were used to support the overlying rocks and to avoid collapsing of the galleries. Credit: Secret de Paris. Figure 5 (right). The galleries of the old quarries were filled with the buried from the Parisian cemeteries. The remains were neatly stacked into blocks with the skulls used as decoration. Marble sign were placed to remind visitors of the origin of the bones. Credit: Anouk Beniest.

For over 150 years, parts of the catacombs have been accessible so people could pay tribute to their dead ancestors. During periods of civil unrest, people would use the old quarries as hide-outs. This was of course not without any risk; people could easily get lost and never see daylight again. In calmer periods, people would still search for ways to get inside, to party all night, go on adventure or just enjoy the silence without leaving the city. In 2005, part of the catacombs was renovated and 1.7 km of galleries is now open for public. The other 300 km of abandoned quarries remains closed, and only those who know the secret entrances dare to descend into these ancient galleries, where Pierre used to mine his limestones and Jean dumped his load of bones.